A new MIT model shows that AI is changing work faster than governments, companies, or workers can respond, and it will affect far more jobs than most people think.

As someone with expertise both in technology (including AI, as I have a number of AI-related patents and have built AI products) and careers, I’ve had a somewhat unique vantage point in seeing the impact AI was going to have on the labor market. I’ve written extensively about this across multiple articles, but it comes down to three central ideas.

1) It’s not about AI replacing an entire job, but about chipping away at parts of the job to make it more efficient; this will reduce the number of people needed in that role (see “Why AI Isn’t (Yet) Ready to Take Your Job”).

2) The pace of change will be unprecedented (see “No, AI Isn’t Going to Kill You, but It Will Cause Social Unrest –- Part 1”).

3) Small changes, and ones we’re likely to miscalculate, if not miss completely, will have large impacts (see “The Coming AI Recession: Looking Over the Cliff of Technological-Based Job Loss” and ”The Path to Hell Is Paved with AI”).

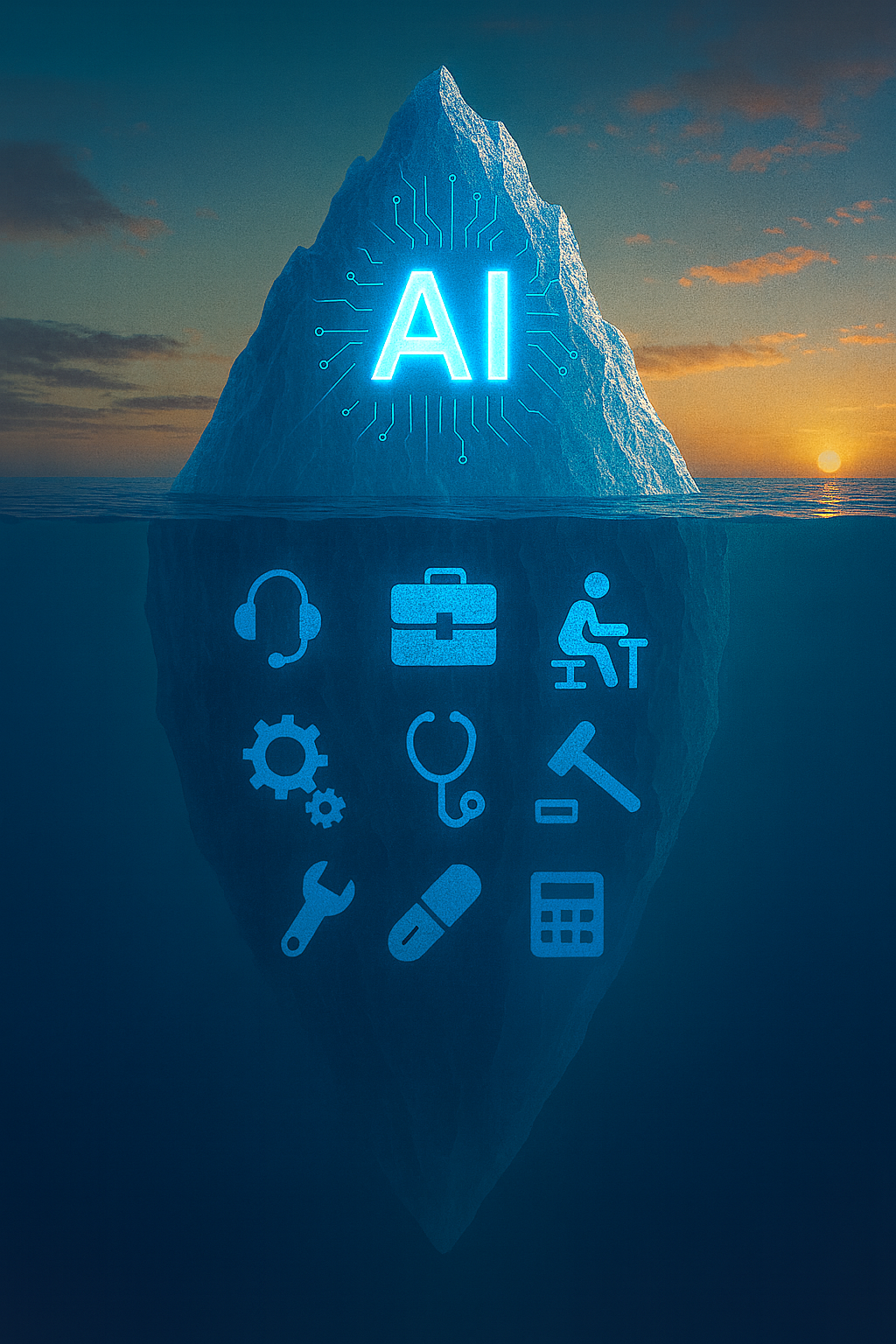

Recently, I wrote the article “The Canary in the Code Mine: What Tech’s Job Slump Means for the Rest of Us” which analyzed what’s happening with tech jobs and how tech is a leading indicator of problems for other industries. Enter MIT’s Project Iceberg, which just put out a report entitled “The Iceberg Index: Measuring Skills-centered Exposure in the AI Economy.” Their work uses a very sophisticated methodology, detailed modeling, and provides a much more rigorous analysis behind similar predictions. I don’t normally write articles that just summarize someone else’s work, but impactful ones like this one are worth covering.

In “The Canary in the Code Mine: What Tech’s Job Slump Means for the Rest of Us” I noted that tech jobs have been some of the first impacted by advances in AI, along with call centers. The authors of the report noted, “AI systems now write over a billion lines of code each day, exceeding human developer output.” (To be fair there’s still an interesting debate about the long-term impact of such code; I’ll cover that in the future article.) But that’s just the tip of the iceberg, which is the motivation behind the project’s name; the true impact will be much, much bigger.

In the study, they broke down jobs into more than 32,000 distinct skills. Then they modeled 151 million workers across 923 occupations in 3,000 counties; each worker is modeled as an agent (in other words, 151 million distinct entities in the simulation). Using agent-based modeling (itself a type of AI, but different from an LLM) they could run predictions on how technology and policy changes can impact the labor market. The key takeaways are as follows.

First, the authors argue that we can’t accurately measure AI’s impact right now; existing metrics like GDP and unemployment are not sufficient. As an example (mine, not an example from the report), during the industrial age we would count the number of factories, the people employed in those factories, and the output of those factories. For example, as the automotive industry was automated, we could see the ratio of workers per car produced in a given year. We have no measurement of how much economic output AI is producing. Economists measure productivity by looking at newer TVs, comparing them to older ones, and determining how much better the newer TVs are, to determine productivity improvements. They can compare two products built in different years and measure the improvement (even if it’s not an exact science). When AI automates some healthcare paperwork, giving medical staff more time with patients, we don’t currently have a way to measure that. Since LLMs are impacting the service industries, we can’t measure it as easily as we did for physical goods.

Second, adapting to the change will be much harder. They write, “evidence suggests workforce change is occurring faster than planning cycles can accommodate.” Combined with the lack of appropriate data noted above, it means policymakers are flying blind. I’ve been arguing for years that we will need massive retraining of the labor force, from both the public sector and private sectors. But without appropriate visibility into the changes and needs, programs will be slower to set up and/or misguided.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, is the iceberg itself. Icebergs famously have most of their mass hidden below the waterline. What may look like a relatively small iceberg floating in the ocean is actually much larger, just not visible. That’s the main concern here.

The researchers point out that “the technology sector represents more than 30% of the S&P 500’s market capitalization but only around 6% of the workforce.” We already know tech workers are having a tough time. More importantly, they write “Analysis shows that visible AI adoption concentrated in computing and technology (2.2% of wage value, approximately $211 billion) represents only the tip of the iceberg. Technical capability extends far below the surface through cognitive automation spanning administrative, financial, and professional services (11.7%, approximately $1.2 trillion).” In other words, those tech workers are the tip of the iceberg. These other professional services are what’s hidden under the water and represents a much bigger impact to the labor market.

The researchers created the Iceberg Index to measure the ratio of the visible to the hidden impact on labor. The data above is succinctly represented as, “The Iceberg Index for digital AI shows values averaging 11.7%—five times larger than the 2.2% Surface Index.” Put another way, the problem is about five times bigger than it may appear right now.

It should be noted that the study explicitly said, “validation correlational rather than causal.” This means it doesn’t technically prove that AI improvements or policies caused the results, merely that they are correlated. Nevertheless, it seems a safe bet to believe that they are since the causal mechanisms are straightforward and well-understood. At the very least, we can’t ignore an impact of this size waiting for causality to be proven.

What wasn’t mentioned in the report, and I don’t believe is taken into account in the model, are the secondary effects. For example, suppose a business park cuts the number of employees working there by one-third. It means the businesses supporting them, such as cleaning services, local lunch places, after-work bars, etc. will all see revenues decline and may experience ripple layoffs. In theory, the money saved from fewer employees will simply shift to the shareholders of the companies employing AI and shareholders of AI companies themselves. Unfortunately, trickle-down economics has been proven to be a mirage. Even when it does work, I’ve argued in those previous articles that there will be a significant delay between job loss and job creation, on the order of years (possibly as much as five to ten years). It should be noted that the iceberg index is especially important to US states with lower tech labor as a starting point, since those states have the largest percent of the labor in the part of the iceberg hidden under the water.

In short, the impact of AI is likely to be bigger and come faster than most people thought. LLMs have already been setting adoption records, which means impacts from that adoption will also set records. Even if your job isn’t impacted today, it likely will be soon, directly or indirectly.

Society needs to prepare. More than any other time since the Great Depression, we need improved social safety nets and support for retraining and entrepreneurship. Local, state, and federal governments need tax policies to mitigate the lost wage revenue. Importantly, these new revenue sources will provide the funding for the needed retraining. During the Great Recession, I taught at the SUNY Levin Institute in a program, funded by the NYC Economic Development Council, to retrain professionals whose jobs were lost and never coming back. We need programs like that on a national scale, and we need to start piloting those programs today.

Individually, people need to recognize that their value proposition to companies will shift. The parts of your job that can be automated will no longer differentiate you in the labor market as I wrote about in “Teach Your Kids to Program, but Don’t Teach Them to Be Programmers” (programming is just the example, it's written about skills in the face of AI generally). Strengthening your communication, teamwork, leadership, networking, and other professional skills is going to be key to staying ahead of the tsunami of change.

It’s critical to learn about corporate culture before you accept a job offer but it can be awkward to raise such questions. Learn what to ask and how to ask it to avoid landing yourself in a bad situation.

Investing just a few hours per year will help you focus and advance in your career.

Groups with a high barrier to entry and high trust are often the most valuable groups to join.